Student Demonstrations for Equal Rights

Marker at the SW corner of Green St. and Wright St.

Despite increasing numbers of African Americans matriculating into the University of Illinois in the 1930s and 1940s, discrimination was rampant on campus and in Campustown. Black students were prohibited from eating in dining halls and local eateries, forcing many students to walk 30 minutes each way for meals in the North End, Champaign-Urbana’s African American neighborhood.

In 1936, Black fraternal organizations, and community and religious leaders—with support from a few campus administrators and faculty members—opened a cooperative lunchroom in an attempt to service Black students. The white community and many university affiliates were unsupportive, and it eventually closed. In 1937, students brought a lawsuit against a Campustown confectionary store for discriminating against African American students, but the case was decided in favor of the business. Albert R. Lee—known as the university’s unofficial Dean of African American Students—advocated on behalf of Black students, and they were finally allowed to eat in the Illini Union basement when it opened in 1941. They continued to encounter overt and institutional racism on campus and in surrounding restaurants, theaters, barbershops, and other businesses.

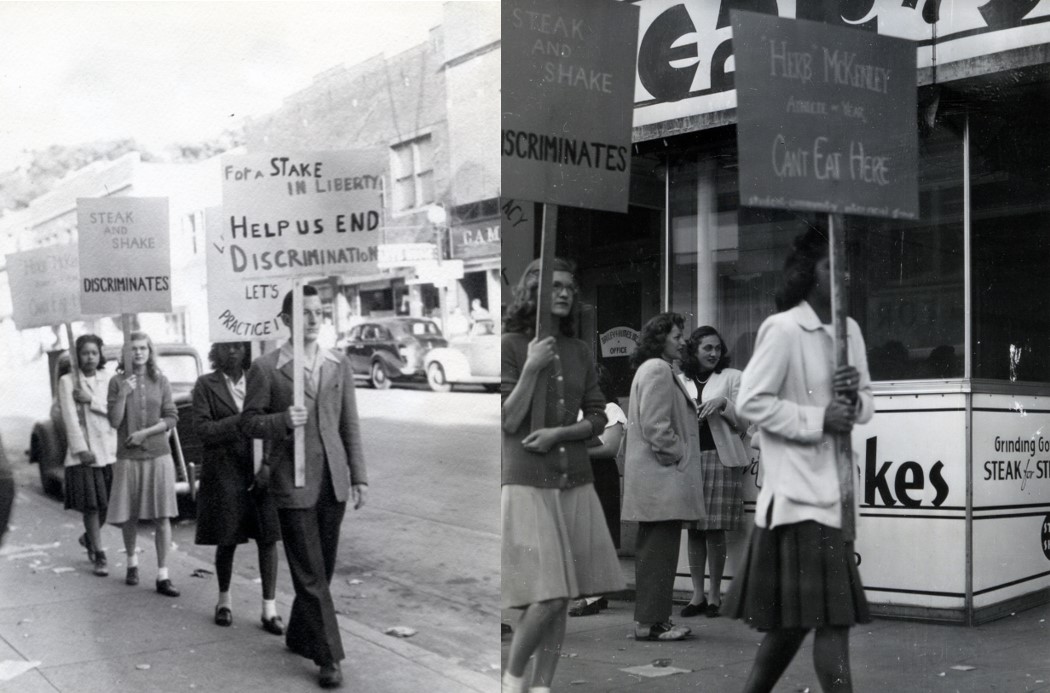

All was not lost. With the G.I. Bill in effect after WWII, many Black veterans attended the University of Illinois and pushed for better conditions. In 1945, an interracial group of campus veterans, students, Black residents, and university faculty formed the Student Community Interracial Committee to address racist policies. The Committee wrote letters, submitted petitions and affidavits, documented unequal treatment, staged sit-ins, filed civil suits, and practiced other non-violent strategies to address discrimination. In the summer of 1946, they picketed Campustown businesses and threatened lawsuits. By fall, the last five restaurants in Campustown agreed to open their doors to African Americans. The Committee dissolved in 1951, but the work was not over. New groups like the Student Human Relations Council formed and, with the Black community, charged forward against discrimination on campus and throughout Champaign-Urbana.

This trail stop is sponsored by:

SOURCES:

Cobb, Deirdre Lynn. “Race and Higher Education at the University of Illinois, 1945 to 1955.” Urbana, Illinois. UMI Company. 1998.

Decade:

1940-1949

People:

- Albert Lee

Location(s):

- University of Illinois, Illinois

Additional University of Illinois Trail Sites