University of Illinois Alumni

1214 S 1st St, Champaign

Since 1900, when William Walter Smith became the first African American to graduate from the University of Illinois, many African Americans who attended the University have gone on to become important leaders, innovators, artists, and thinkers. This page features some notable University alumni. Please check back periodically as we continue to include more information.

Decade:

1900-1909

People:

- Beverly Lorraine Greene

- Maudelle Tanner Brown Bousfield

- St. Elmo Brady

- Walter T. Bailey

Location(s):

- University of Illinois, Illinois

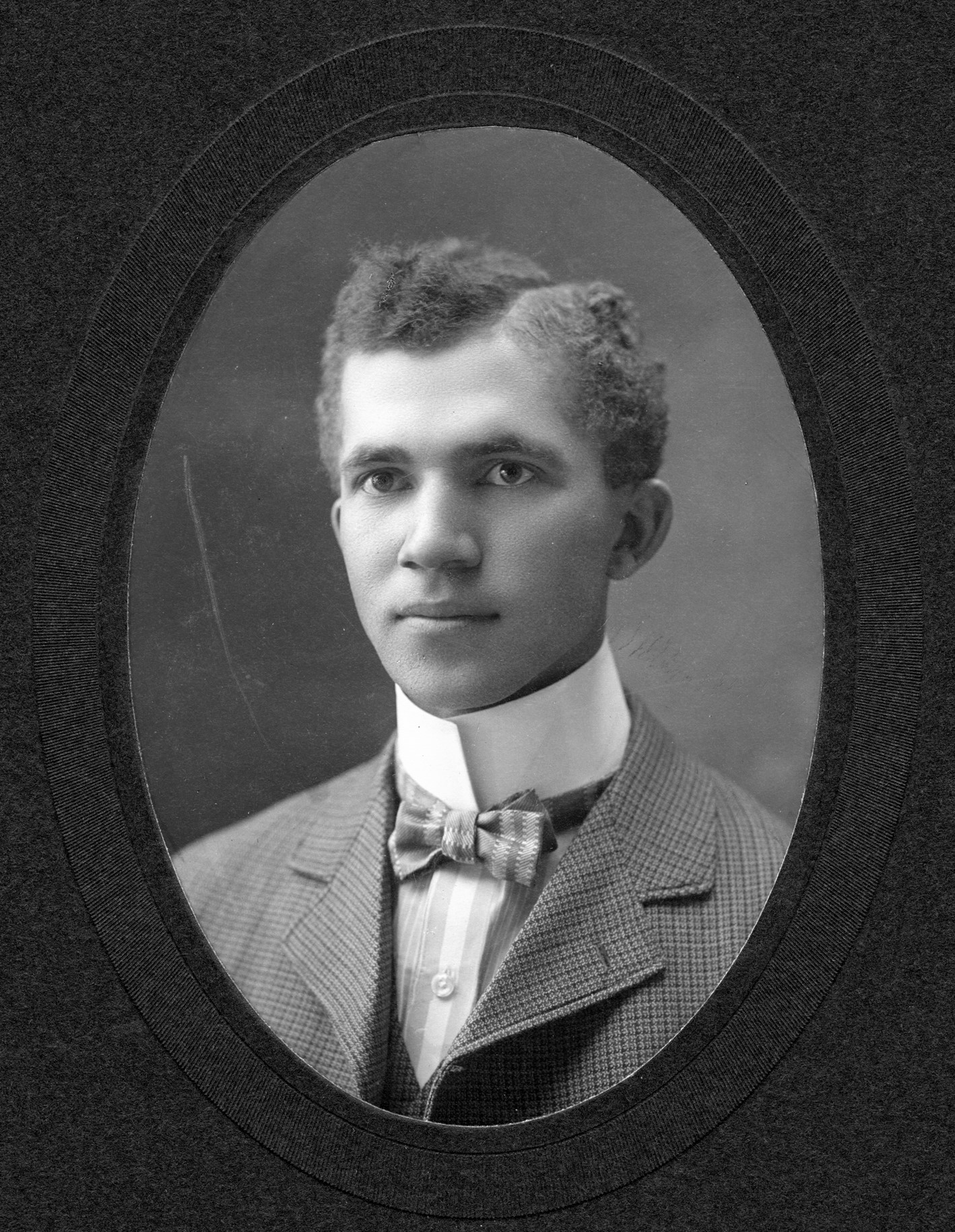

Walter Thomas Bailey was born in 1882 to Emanuel and Lucy Reynolds Bailey in Kewanee, Illinois. He entered the University of Illinois in 1900 and graduated in 1904, becoming the first African American with a bachelor of science degree in architectural engineering from the university and the first licensed Black architect in Illinois. After graduating, he married Josephine McCurdy on October 15, 1904. They would have two daughters, Edith Hazel and Alberta Josephine.

In 1905, Bailey was noted for assisting with the design of Colonel Wolfe School, which was built in the Prairie Style. The building is currently located at 403 E. Healey St. in Champaign. From Champaign, Bailey relocated to Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute where he headed up the Mechanical Industries Department while supervising the planning and architectural design of the Tuskegee Institute’s campus. In 1910, he was recognized by the University of Illinois with an honorary master’s degree in architecture.

Bailey eventually opened his own architectural office and practiced in both Memphis, TN, and Chicago, IL. In 1922, he was commissioned by the Knights of Pythias to design the eight-story National Pythian Temple in the heart of the south side of Chicago, though the building was demolished in 1980. His last major project, in 1939, was to design the Black-led First Church of Deliverance in Chicago located at 4315 S. Wabash Avenue in Chicago. The church is noted for its sleek streamline Art Moderne design with a lack of ornamentation. A design style developed out of Art Deco, it is a unique departure from the design of most other houses of worship. (Note that the double towers were added later after his death.) In 1994, the city of Chicago gave the church “Chicago Landmark” status because of its architectural and cultural significance.

Bailey died on February 21, 1941. However, his legacy and impact remain visible in the buildings he helped design and inspire across the nation.

Sources:

Preservation and Conservation Association: http://pacacc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Summer-2018.pdf

University of Illinois: https://faa.illinois.edu/walter-t-bailey

Walter Thomas Bailey: Champaign-Urbana, Local Wiki; website: https://localwiki.org/cu/Walter_Thomas_Bailey

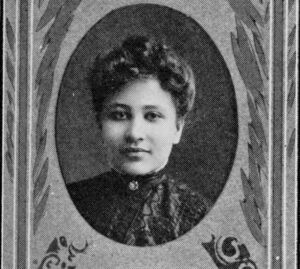

Maudelle Tanner Brown Bousfield was born on June 1, 1885 to educators Charles H. Brown and Arrena Isabella Brown. Her intelligence and talent were evident from a young age. As a teenager, she became the first African American student to attend the Charles Kunkel Conservatory of Music in St. Louis. Then in 1903 she became the first African American woman to enroll at the University of Illinois. As a student, she excelled academically and helped pay for her education by tutoring other students in mathematics and playing piano at sorority dances. In only three years, she graduated from the university with honors, earning degrees in astronomy and mathematics.

Bousfield taught mathematics after college, and eventually became the first African American Dean of Girls in the Chicago Public School system in 1920. Over the next three decades, she enjoyed tremendous professional success. She passed the principal’s examination in Chicago with high marks, became the first Black principal in Chicago at Keith Elementary School, served as principal of Douglas Elementary School, became the first Black principal of a Chicago high school at Wendell Phillips High School, served as the national president of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., and received a master’s degree in education from the University of Chicago. Meanwhile, she published academic articles advocating for African American students and served on numerous boards and committees, including as an examiner on the Chicago Board of Education. She served at Wendell Phillips with great distinction until her retirement in 1950.

She received widespread recognition and numerous awards throughout her life and after her death in 1971. In 1965, she became an honorary member of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society at the University of Illinois, and in 2013 the university opened a new residence hall named in her honor. She is remembered today as an outstanding talent, fierce advocate, and groundbreaking pioneer whose work touched countless lives.

Sources:

University of Illinois. “Maudelle Brown Bousfield.” https://gec150.web.illinois.edu/1900s/maudelle-brown-bousfield/

University of Illinois. “The Courage to Be First.” https://storied.illinois.edu/the-courage-to-be-first/#!

Image Credits:

- Maudelle Tanner Brown Bousfield, 1907 Illio (yearbook), no. 13, pp. 49 (University Illinois Urbana Champaign Library, Urbana, IL)

- Bousfield Hall (University Housing at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign)

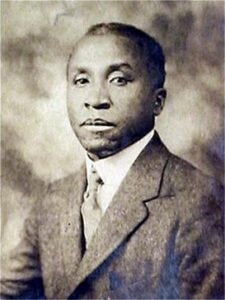

Dr. St. Elmo Brady was born on December 22, 1884, in Louisville, Kentucky. He later received a scholarship to attend the University of Illinois to further his education under the tutelage of Professor George Beal. Over the course of his graduate studies, he published three scholarly articles. He received his master’s degree in chemistry in 1914 and his Ph.D. in 1916 from the University of Illinois. He became the first African American to obtain a Ph.D. in chemistry in the United States. His Ph.D. research was conducted at Noyes Laboratory (505 S. Matthews Avenue, Urbana).

After receiving his bachelor’s degree from Fisk University in 1908, Dr. Brady began teaching at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute (now Tuskegee University). He was greatly influenced by Thomas W. Talley, a forerunner in the teaching of science. Throughout his career, Brady went on to teach at several universities, including Tuskegee Institute, Howard University, and Fisk University. At Fisk University, he developed the first chemistry graduate program in a historically Black college.

On February 5, 2019, the American Chemical Society installed a National Historic Chemical Landmark plaque at Noyes Laboratory to honor Dr. St. Elmo Brady’s life and work.

To learn more about St. Elmo Brady, watch the video below from the University of Illinois, or visit the University of Illinois’ Department of Chemistry website (https://chemistry.illinois.edu/spotlight/alumni/brady-st-elmo-1884-1966) and the American Chemical Society’s website (https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/st-elmo-brady.html).

Image Credits:

- Undated Portrait of St. Elmo Brady (University of Illinois Archives)

- St. Elmo Brady in a chemistry lab, possibly at Fisk University, ca. 1950 (University of Illinois Archives)

Beverly Lorraine Greene was born in 1915 to James A. and Vara Green in Chicago, IL. She became the first African American woman to receive a bachelor of science degree in architectural engineering from the University of Illinois in 1936. While an undergraduate, she became the only African American and only woman member of the student chapter of the American Society of Civil Engineers. She was a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority and the Cenacle, a Black literature and drama society on campus. In 1937, she received a master’s degree from the university in city planning and housing. Throughout her career, Greene was an advocate of African American female professionals.

After graduation, Greene worked for the Chicago Housing Authority as one of the first African Americans in the agency. She received her Illinois architect’s license in 1941, and is believed to be the first licensed Black female architect in the United States.

Greene moved to New York City to work on the Stuyvesant Town housing project in lower Manhattan. Though it was announced that African Americans would not be allowed to live there, Greene was hired for the project as architect. She earned another master’s degree in architecture from Columbia University in 1945. Afterward, Greene collaborated with various noted architectural firms. Among her accomplishments was hospital design, assisting with the design of the theatre at the University of Arkansas in 1949-1951, and an arts complex at Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, NY, in 1952. In 1953, she also worked on alterations to the Carson, Pirie, Scott and Co. Department Store in Chicago, and she designed the Unity Funeral Home in Harlem where the two-day wake for Malcolm X was held in 1965 with more than 30,000 people attending. She also worked with architect Marcel Breuer on the UNESCO United Nations headquarters in Paris before its completion in 1958.

Greene was working on designs for New York University campus buildings at University Heights when she died on August 22, 1957 at the age of 41. Her funeral was held at the Unity Funeral Home she helped design.

“Beverly Lorraine Greene,” by Roberta Washington, Pioneering Women of American Architecture; website: https://pioneeringwomen.bwaf.org/beverly-lorraine-greene/

Optima Forever Modern. “Women in Architecture: Beverly Lorraine Greene.” https://www.optima.inc/women-in-architecture-beverly-loraine-greene/

University of Illinois Distributed Museum. “Beverly Lorraine Greene.” https://distributedmuseum.illinois.edu/exhibit/beverly-loraine-greene/

Wikipedia. “Beverly Lorraine Greene.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beverly_Lorraine_Greene

Additional University of Illinois Trail Sites