Early Achievements in Homer & Southeastern Champaign County

500 E. 2nd St., Homer

Homer, Illinois, has a rich history as a village where many early African Americans in Champaign County could gather, work, recreate, and build successful lives for themselves and their families. Many prominent African American businesspeople, intellectuals, and community leaders passed through or came from Homer.

African Americans began gradually moving into East Central Illinois in the late 1820s and into Champaign County by 1850. In the 1820s and 1830s, they mainly came from the southern states of Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Virginia, both as enslaved and free people. According to Illinois laws known as the Black Codes, enslaved African Americans were required to have a contract of termed indenturement after entering the state, or they had to be released.

Mary Neal, known as Pol, is believed to be the earliest African American in the area around 1832. She was one of five individuals enslaved by Abraham Sandusky (sometimes reported as Sodowsky or Sonowsky) in Bourbon County, Kentucky, before he moved his family to Carroll Township in the southwestern corner of Vermilion County. While pregnant, Mary accompanied the family north, and it was assumed that she was freed prior to the move. It was said that Mary was adopted by Sandusky, and she even appeared in some written histories of Vermilion County as one of his children. However, according to census records, she remained a “housekeeper and nanny” to the Sandusky family through multiple generations for the rest of her active life, living close to the border of Champaign and Vermilion Counties. Her son, Gabriel Neal (1832–1902), was born soon after she arrived in Vermilion County and went on to become a livestock and cattle dealer earning assets over $10,000 (about $329,902.33 today). He married Sarah Jordan Beechum (1853–1928) on October 12, 1884, and had two known children, a son named Franklin (Frank) and a daughter believed to be named Sarah who died as an infant. By 1900 he moved to Danville, Illinois.

In the 1860 census, 21-year-old James Brown was living as a farm laborer on the Andrew Smith farm and was the earliest African American known in South Homer Township. Across the border in Vermilion County, in Vance Township, the Crawfords lived on the Booker farm, although it’s not known how long they stayed. The Civil War triggered a migration north into Illinois, so that by the 1865 census there were three Black males and six Black females residing within South Homer. Five of the females were employed on the Sullivant farm to the south of the village in what is now Broadlands, and two males and one female were employed elsewhere on the Sullivant holdings.[1] In contrast, the census listed 26 African Americans in Sidney Township.

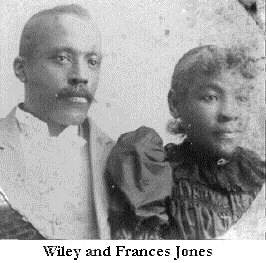

The village of Homer’s African American community began when a lieutenant of the 26th Illinois Volunteer Infantry encountered an enslaved 16-year-old homeless boy while his unit occupied Macon, Georgia, in 1864. William Clayton Custer, just 23 at the time, befriended the boy and took him on as a servant. That boy, named Wiley Jones, later became one of Homer’s prominent businessmen. Jones was born into slavery to Alfred and Martha Jones in rural Georgia about 1848. He had two sisters, Ellen and Laurat. However, enslaved family members could be separated and sold, and Martha “remarried” before the Civil War to Peter Lewis. After meeting Custer, Jones made his way to Homer. He went to school in the Homer school system, then learned the barber trade, and became a part of various shops on Main Street, eventually owning his own barbershop and becoming a respected small businessman. Jones married St. Frances (Fannie) Roberson in Homer on November 29, 1877, and the ceremony was performed by Ben Towner at the home of Rev. Whitlock. Frances and her daughter, Mary Morgan, had come to Homer from Michigan after having been enslaved in North Carolina. She worked at odd jobs, but later worked as a domestic for a number of years in the home of Congressman Joseph Cannon of Danville.[2]

Jones served on the Board of the Homer Savings and Loan, was nominated for the Village Board several times, and became a co-founder of Homer’s Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) post He was an honorary member of the 26th Illinois Infantry, elected by the members of their reunion group. Frances’ daughter, Mary, was the first African American graduate of Homer High School in 1887. Upon graduation, a grand party was thrown for her with friends coming from Danville and Champaign. “They returned home on the midnight trains wishing Miss Mary might graduate often,”[3] the Champaign County Herald observed.

Homer was not the only town in Southeast Champaign County that attracted freed men and women. Lt. James S. Freeman of the 10th Illinois Cavalry returned to Ogden with five formerly enslaved men and their families. From north of Homer, Freeman was a stock raiser who enlisted at Sidney. One of the freedmen, Robert Gregory, became a landholder, farmer and itinerant preacher in the areas of Homer, Sidney, and St. Joseph. Born in Tennessee, Gregory moved north with his wife Sarah and children and farmed north of Sidney. His reputation among the people of the Salt Fork was excellent and he presided over the affairs of the early African American families in the Sidney area, including the Allen, Randall, Faulk, and Beard families. He is buried in the Huss Cemetery east of Sidney.

Major events organized by the African American community in southeastern Champaign County began in the 1870s with September celebrations of the Emancipation Proclamation and the passage of the 15th Amendment. Initially, many local African American residents traveled to the Sidney celebration of 1877 which brought communities together from Homer, Champaign-Urbana, Philo, and Sidney for music, speeches and a balloon ascension.[4] The Homer Band was even dispatched to the event. Emancipation Day celebrations were held in various locations in the 1880s, including Homer in 1886. Civil War veteran Samuel Persons organized that event.[5] That same year, Sidney had another large celebration at Coles Hall.[6] By the 1870s and 1880s, debating societies were popular in Homer, including a debating society of Homer’s African Americans. On November 6, 1880, the group met to debate “Resolved, that Jefferson Davis did more to free the slaves than Lincoln.” Al Robinson, a Civil War veteran from Sidney, spoke for the affirmative and Samuel Persons for the negative. The Times of Champaign noted that “Robinson got laid out.”[7] Tickets to these events were sold to all. Other issues debated included, “Resolved, that a man will do more for money than he will for love,” And “Should the colored people of the north assist the colored people of the south?” Al Robinson worked hard to ensure the debating society’s topics were timely to African Americans.

By 1880, African Americans led Homer’s barbering trade. John Williams worked on Main Street in a small room adjoining Mudge’s Drug Store in 1877. W. Chandler moved from Champaign to establish a shop in the fall of 1879. Samuel Persons and Wiley Jones each had their shops in the village in 1880.[8] The newspapers treated each of the Black businesses with respect and always wished them well. These barber shops prospered and became points of pride for members of the African American community in Homer, most of whom worked primarily in laundry, general labor, shoe repair, or as farmhands.

The local newspapers and local correspondents for newspapers in Danville and Champaign-Urbana covered African Americans and their social lives. While other newspapers identified African Americans by race, The Homer Enterprise did not.

Another significant African American who settled in Homer was Samuel Persons. He served as a corporal in the Indiana’s 28th Regiment USC Infantry, and he was seriously wounded in the Civil War. In 1881 Persons was awarded a back pension of $1,536 with which he purchased a home from Mort Smith in the western part of the village.[9] Samuel owned a barbershop and lived in the village with his wife, Cynthia Allen Persons. Dedicated to intellectual development, Persons formed a debating society in the late 1870s or 1880s. He and his wife lived in the village until he died of “lung fever” in 1893. Corporal Persons was one of the charter members of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) post in Homer and is buried in GAR cemetery.[10] John Petteford, another Civil War veteran and settler in Homer, is also buried in the GAR cemetery.

Another formerly enslaved man and Civil War veteran south of Homer was George W. Smith. George Smith was born into slavery near Selmar, McNairy County, Tennessee, on December 3, 1836. At the age of nine, he and his six brothers and sisters were sold from his mother. He was sold for $501.50 to a family that assigned him the task of accompanying the owner’s children to school and back.

It was a crime to educate enslaved people in the antebellum south, but Smith would stay by the schoolhouse absorbing what he could hear from the teacher inside. One day, the teacher, shaming a student who struggled to answer a question, said that even Smith knew the answer. Smith did know it and replied. The other children took pride in Smith’s knowledge, but Smith’s owners were informed and ordered the teacher to refrain from educating him. The teacher still gave Smith books surreptitiously, telling him to hide them under his shirt.

As Smith grew, he apprenticed as an assistant miller and soon became the miller when his superior was fired. He continued milling until the spring of 1862 when the Civil War began. After learning that a group of rebels were coming to kill him because of his knowledge of the area, he fled the area with his rifle in tow. He walked to Shiloh and became a scout in the Union army. He served in Tennessee and Mississippi as a guide for General Logan, but as his health declined he left the Army and relocated to Springfield, Illinois.

Smith married Mrs. Mary E. Gaines in Springfield and began farming in summer and chopping wood in winter. He was a very strong man, some saying he had the strength of two men. He would walk four miles to the woods and spend the day working, producing three and a half cords of wood per day. In the spring of 1876, he moved to Broadlands and by December of 1877 he was farming the land that would be his home. The first mention of George Smith in Homer was in early August 1877 when his six-year-old son, one of seven children, was playing on a fence and fell, breaking his neck. The boy was killed instantly.[11]

Smith worked the swampy prairie land over the years to pay off his first 80 acres and add to his property. He raised hogs and became well known for his breeding stock. Smith’s farm was known as “The Trail,” and he was one of the first farmers to adopt drainage tile, using his drained lands for raising clover as well as corn.

Smith never forgot his educational experiences as a boy and emphasized the importance of education among his children. Smith was known to spend more money on his children’s education than anyone else. His son, William Walter Smith, graduated from Homer High School in the class of 1895. William was the first African American graduate at the University of Illinois in the class of 1900 and became an executive with the Armour Corporation and, later, American Portland Cement Works in Philadelphia. Another son, Fred, became an attorney in Omaha, Nebraska. George’s son Charles took over the farm and became an important stock and horseman in the county.

Smith, a Republican, became somewhat important in Republican Party circles in the county. He owned 440 acres of some of the most productive farmland and became one of the wealthiest farmers in the area.[12]

When George W. Smith died on December 29, 1911, his funeral and burial at the Ridge Cemetery was one of the largest held in that section of the county. A biography was published in the Danville Press-Democrat a week after his death attesting to his achievements and the legacy he left in the county.[13] While Smith lived just northwest of Broadlands, his name and legacy lived on in Homer for decades as a determined farmer and someone who overcame enormous odds to become a wealthy man.

This trail stop is sponsored by:

SOURCES:

[1] Illinois State Census Champaign County, 1865, Urbana Archives. This census was conducted on July 3, 1865.

[2] Danville Commercial-News, March 7, 1914, page 2.

[3] Champaign County Herald, May 11, 1887, page 13.

[4] Danville Commercial, September 27, 1877, page 8.

[5] Danville Weekly News, July 23, 1886, page 6.

[6] Danville Weekly News, September 24, 1886, page 1.

[7] The Times, November 11, 1880, page 1.

[8] Danville Commercial, September 13, 1877, page 8; The Times, September 27, 1879, page 3.

[9] Champaign County Herald, November 30, 1881, page 5.

[10] See Meeting Minutes of the G.A.R., May 29, 1883, page 3, Homer Historical Society.

[11] Champaign County Gazette, August 8, 1877, page 4. The Gaines family, related by marriage to Smith’s wife, also came to the area. Albert Gaines was a son-in-law of Jacob Earnest. Jacob Earnest’s wife lived with her daughter, Mrs. Gaines, after Jacob Earnest’s death in 1910.

[12] Danville Press-Democrat, January 7, 1912, page 1.

[13] Danville Press-Democrat, December 30, 1911, page 3. Charles Smith was interviewed in 1968. It was estimated that George Smith was, at the time of his death, the wealthiest African American in Illinois. See Homer Enterprise, September 12, 1919.

Decade:

1850-1859

People:

- Anthony Albert Gaines

- Frances Jones

- George W. Smith

- James Brown

- Mary Gaines

- Mary Neal

- Samuel Persons

- Wiley Jones

- William Walter Smith

Location(s):

- Homer, Illinois

Additional Homer Trail Sites