The Ellis Drive Six and School Integration

1108 Fairview Ave, Urbana, IL

In the 1960s, after realizing that their children were not receiving an equal education at James Wellen Hays Elementary School, neighbors Carlos and Willeta Donaldson, Paul and Shirley Hursey, Jo Ann Jackson, and Rev. Dr. Evelyn Underwood (then known as Evelyn Burnett), formed the Hays School Neighborhood Association. They lived in the Dr. Ellis Subdivision—the first subdivision of single-family homes in Urbana developed for African Americans—and met, researched, and strategized about meeting with the Urbana School Board to address educational disparities for African American children and advocate for school integration. These neighbors became known as the Ellis Drive Six.

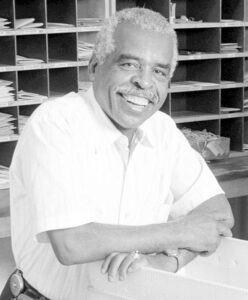

They conducted surveys and collected evidence about outdated textbooks, disproportionate numbers of dropouts, racist teaching practices, and other inequities, but they knew more support would be needed to persuade Urbana School District 116 to change. Then, while working as University of Illinois mailmen in 1965, Carlos and Paul learned about a dissertation that validated their findings by identifying and measuring achievement gaps between African American students attending Hays School and other schools in the district. It was exactly what they needed to petition the School Board.

Their efforts to challenge and stand up against the all-white School Board were successful. In 1966, 12 years after Brown v. Board of Education declared that “separate-but-equal” schools were not, in fact, equal, Urbana School District 116 became the first school district statewide to institute a desegregation program. Many African American children who attended Hays School were bused to other schools in the district, and children of University of Illinois students who lived in Orchard Downs were bused to Hays. While there were challenges during the implementation of the integration program, most issues were resolved by 1968. Hays School was renamed as the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary School in 1970, and the school remains open to this day.

The Ellis Drive Six comprised individuals who believed in the power of unity to enact change, and their community advocacy extended beyond school reform.

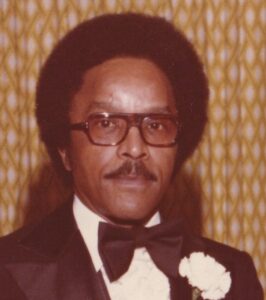

Paul and Shirley Hursey led demonstrations protesting discriminatory housing policy. At one time, homes purchased by African Americans that were not located in the predominantly African American North End neighborhood (which contained the Dr. Ellis Subdivision), would be physically moved to the North End. In protest of these racist housing practices, the Hurseys led demonstrations where they would use cars to blockade roads on which the houses were to be moved. The Hurseys were also deeply involved in the community. Mr. Hursey was the first African American to serve on the Urbana City Council and was instrumental in bringing equal services to the North End. He was elected in 1962 and served multiple terms. Mrs. Hursey was active in civic and church activities in the Champaign-Urbana area.

Carlos and Willeta Donaldson were also deeply involved in their community. Mr. Donaldson served on the Urbana School Board from 1981 to 1985, and Willeta Donaldson served on Urbana’s Human Rights Commission. Both were University of Illinois employees and instrumental members of the PTA and PTO.

Rev. Evelyn Underwood, PhD was the first African American School Board member for Urbana School District 116. She was elected in 1968 and served for 12 years. Alongside her husband, Pastor King James Underwood, she helped shepherd the New Free Will Baptist Church as Associate Minister.

Carlos Donaldson Willeta Donaldson Paul Hursey Shirley Hursey

Jo Ann Jackson Rev. Dr. Evelyn Underwood

Courtesy of the Champaign County Archives at The Urbana Free Library, interviews with Paul Hursey are available below. The first interview was conducted on March 2, 1982, and a transcript is available here. The second interview was conducted on August 1, 1983.

This trail stop is sponsored by:

SOURCE:

Champaign County Archives at The Urbana Free Library. https://urbanafreelibrary.org/local-history/collections/oral-histories.

Decade:

1960-1969

People:

- Carlos Donaldson

- Evelyn Underwood

- Jo Ann Jackson

- Paul Hursey

- Shirley Hursey

- Willeta Donaldson

Location(s):

- Urbana, Illinois

Additional Urbana Trail Sites