Frederick Douglass’ Visit to Champaign

One Main Plaza, Champaign, IL

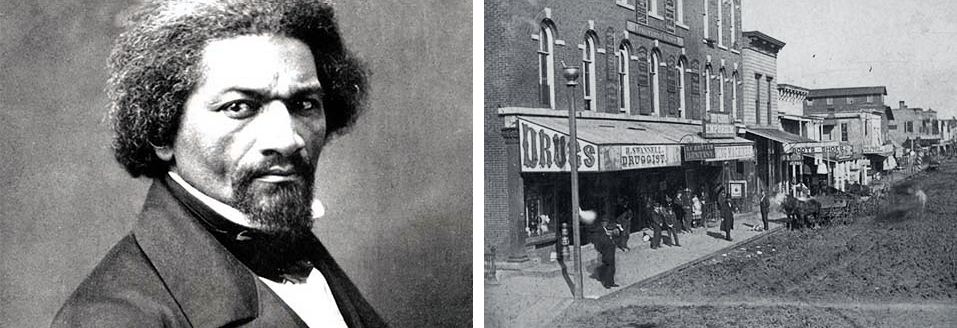

Frederick Douglass visited Champaign on February 15, 1869, at Barrett Hall, located above what was Henry Swannell's Drug Store, now One Main Plaza. His topic was Self-Made Men. It was reported that, “His wit was keen and sparkling, his humor dry and effective, and his logic and argument as clear as that of the most polished orator in the land.” Champaign County Gazette, February 17, 1869, page 1

Four years after the end of the Civil War, the famous formerly enslaved abolitionist, publisher, public speaker, and soon to be diplomat Frederick Douglass addressed an audience at Barrett Hall. It was Monday, February 15, 1869. The hall was located on Barrett Block above what was Henry Swannell’s drug store, now One Main Plaza. Douglass’ topic was Self-Made Men. The event was covered by the local newspapers, the Champaign County Gazette and Union, in a small one-paragraph description in which the reporter stated:

“No man has ever yet addressed an audience in this city and received the marked attention that did Mr. Douglass. He handled his subject most skillfully and impressed his audience with the points of his arguments in the most happy manner…His wit was keen and sparkling, his humor dry and effective, and his logic and argument as clear as that of the most polished orator in the land.”

— Champaign County Gazette and Union, February 17, 1869, page 1

“Self-Made Men” was one of his favorite topics. He delivered variations of this speech over 50 times in the last half of his life, beginning in 1859. While the main text remained the same, Douglass added contemporary references with each rendition. For example, in 1893 he quoted the poem, “The Path”, by African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, from Dunbar’s first published book of poetry Oak and Ivy. Given two years before Douglass’ death, the 1893 oration took place at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The most acknowledged and known of the “Self-Made Men” versions, it’s used here to help explain Douglass’ beliefs.

“Self-Made Men“, no matter the version, reflected the concept of American individualism and was the centerpiece of his proudly embraced personal beliefs. Like Benjamin Franklin, another self-made man who came before him, he believed independence, pride, and individual and economic freedom were the natural consequences of becoming a self-made man—and the root of what became known as the American dream, which everyone, regardless of race, had not just the right, but deserved the right to pursue.

Born Frederick Washington Bailey to an enslaved woman and an enslaver white father in 1818, Douglass understood that it was not just luck, status, position, power, wealth, attained knowledge, connections, or usefulness that made the man—rather, a man was made by considerable physical and mental effort. For him, self-made men were:

“In fact…men who are not brought up but who are obliged to come up, not only without the voluntary assistance or friendly co-operation of society, but often in open and derisive defiance of all the efforts of society and the tendency of circumstances to repress, retard and keep them down…They are…indebted to themselves for themselves. If they have ascended high, they have built their own ladder…”

— Fredrick Douglass, “Self-Made Men,” 1893

Asked about African Americans he stated:

“I have been asked “How will this theory affect the negro?” and “What shall be done in his case?” My general answer is “Give the negro fair play and let him alone…[However] it is not fair play to start the negro out in life, from nothing and with nothing, while others start with the advantage of a thousand years behind them…[G]ive him a chance to do whatever he can do well. I can…assure you that he will not fail.”

— Fredrick Douglass, “Self-Made Men,” 1893

Douglass didn’t believe that self-made men were or should be totally independent. His experience in slavery and during the period before the Civil War taught him that these men who had ‘pulled themselves up by their boot straps’ needed to form brotherhoods—interdependent groups—that upheld moral principles, honor, integrity and affection for one another. He saw himself as a part of a larger entity of mankind connected by these brotherhoods. This hard work, effort, and self-dependence were his prerequisites for success. As he stated:

“My theory of self-made men is, then, simply this: that they are men of work. Whether or not such men have acquired material, moral or intellectual excellence, honest labor faithfully, steadily and persistently pursued, is the best, if not the only, explanation of their success.

— Frederick Douglass, “Self-Made Men,” 1893

The event was sponsored by the Library Association of Champaign. Organized less than a year before, in 1868, it was a 40-member organization that paid dues for the use and maintenance of its 300 books and periodicals. Its small library was located in a reading room on the second floor of 7 Main Street, two building east of Barrett Hall. Frederick Douglass’ appearance in Champaign was to raise money for the organization. Accordingly, on the evening of February 15, 1869, the association took in about $254 (approximately $5,265 in 2022 dollars), an impressive amount of money for two towns with a combined population of only around 7,000 (according to the 1870 census). It wouldn’t be until 1876 that Champaign’s public library came into existence with the dissolution of the library association.

Douglass visited Champaign a second time in January of 1872. His visit was announced in advance by the Champaign County Gazette who called him “the African Demosthenes of the Nineteenth Century, the Tawny Philosopher of the Golden Age.” However, the event appears to have received no coverage. Though it’s not known what Douglass spoke about in 1872, it has been speculated that the topic may have been the annexation of Santo Domingo, now known as the Dominican Republic. In 1869, the year that Douglass first spoke in Champaign, President Ulysses S. Grant proposed buying and annexing the island county with a promise of statehood. Then, with an idea of possibly sending African Americans there, in 1871 Grant appointed Douglass as Assistant Secretary to the Commission of Inquiry on the annexation of Santo Domingo. However, the Annexation Treaty failed to pass in Congress on June 30, 1871. Most people who were afraid of the immigration of Dominicans to the United State were opposed it. And, despite his participation, Douglass was against deportation of American Blacks. So it’s unlikely Douglass spoke on annexation. Nonetheless, he did support United States expansionism and Pan-Americanism as long as it promoted effective and egalitarian development to all counties involved. Plus, he travelled the country speaking on the subject, including the United States’ possible assistance in Santo Domingo.

After Douglass’ two appearances, Barrett Hall itself went through a few business changes over its lifetime, including being remodeled as the Champaign Opera House in 1887, and becoming Brown’s Business School in 1900. The hall and building were razed in 1950 to make way for W.T. Grants Department Store. Today, One Main Plaza in Champaign, Illinois, stands in its place.

This trail stop is sponsored by:

Images:

Swannell’s Drug Store, c. 1865, Champaign County Historical Society, Champaign County Archive, Urbana Free Library, Urbana, IL.

Frederick Douglass, c. 1866; Wikipedia, Public Domain

Documents/Sources:

Champaign County Gazette, February 17, 1869 pg. 1.

Champaign Public Library, History; website: https://champaign.org/about/history

“Frederick Douglass: Self Made Man,” Timothy Sandefur, [Washington D.C.: CATO Institute, 2018]

“Fredrick Douglass and the Self-made Man”, 57.47 min. lecture, Timothy Sandefur, 2018, TOS – The Objective Standard; website: https://youtu.be/poaJU1PFv1s (Self-made Man: 09:58 – 24.06min.)

“In 1871, the US almost acquired the Dominican Republic. . .,” Yahoo!, by DeArbea Walker, July 11, 2022; website: https://www.yahoo.com/amphtml/entertainment/1871-us-almost-acquired-dominican-135435379.html

“In C-U, There can ’t ever be enough monuments to Frederick Douglass”, New Gazette (Champaign, IL) December 5, 2012, pp. 1 & 8-A.

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Frederick Douglass, (Dover Publications), 1845.

Sandburn Fire Insurance Maps, Champaign, IL, 1887; University of Illinois Library’s Digital Collections; website: website: https://digital.library.illinois.edu/collections/6ff64b00-072d-0130-c5bb-0019b9e633c5-2

“Self-Made Men,” Wikipedia; website: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-Made-Men

“Self-Made Men,” Speech by Fredrick Douglass, 1872; [Note: The date is incorrect. This is the 1893 version.] Website: www.leeannhunter.com/english/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Douglass_SelfMadeMan1872.pdf

“Self-Made Men,” Speech by Frederick Douglass, 1893; The Speeches of Frederick Douglass: A Critical Edition, Edited by John R. McKivigan, Julie Husband, and Heather L. Kaufman

Fredrick Douglass Papers, “Self-Made Men: Address before the Students of Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Carlisle, Pa.”, 1893, Library of Congress, digital copy: website: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/ms000009.mss11879.00531

Decade:

1860-1869

People:

- Frederick Douglass

Location(s):

- Champaign, Illinois

Additional Champaign Trail Sites